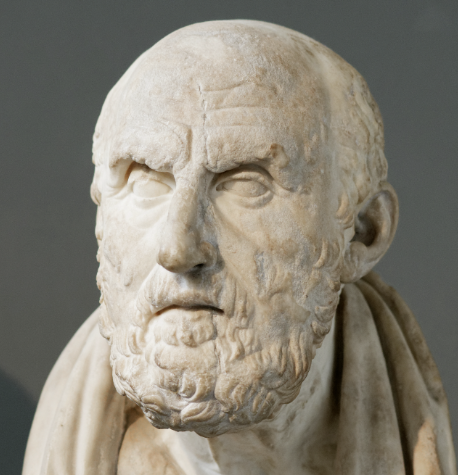

Chrysippus — The Architect Who Built Stoicism into a System (c. 279–206 BCE)

Chrysippus was the mind that made Stoicism intellectually indestructible. If Zeno founded the school and Cleanthes gave it moral gravity, Chrysippus gave it bones, nerves, and a rigorous brain. Ancient philosophers joked that “without Chrysippus, there would be no Stoa” — a joke that was also a sober assessment.

From Exile to Intellectual Command

Born in Soli, in Cilicia (modern-day Turkey), Chrysippus lost his family property early in life and arrived in Athens as a kind of philosophical exile. There he joined the Stoic school, studying first under Cleanthes, whose moral seriousness he admired even as he quietly recognized its theoretical gaps.

Chrysippus was not a charismatic teacher or a poetic soul. He was a relentless thinker — argumentative, precise, and endlessly productive. While others spoke beautifully about virtue, Chrysippus asked how such claims could survive logical attack.

“If there were no Chrysippus, there would be no Stoa.”

— ancient proverb

Logic — The Shield of Philosophy

Chrysippus believed that philosophy collapses without logic. Ethics without clear reasoning becomes sentiment; physics without structure becomes myth. He therefore devoted enormous energy to formal logic, effectively creating propositional logic centuries before its modern rediscovery.

He analyzed conditionals, contradictions, paradoxes, and the structure of valid inference. His aim was defensive as much as creative: Stoicism needed to withstand attacks from Skeptics, Academics, and Epicureans, all of whom delighted in exposing weak arguments.

“If you grant the premises, you must grant the conclusion.”

Physics — A Rational, Living Cosmos

For Chrysippus, the universe was not chaos but a rational, living system permeated by logos — divine reason. Everything that happens follows from necessity, governed by causal chains that express cosmic order. Fate, in Stoic terms, was not blind destiny but intelligible structure.

Human beings participate in this rational cosmos through their capacity for reason. Freedom does not mean escaping causality; it means understanding it and aligning one’s will with nature. A free person consents to reality rather than rages against it.

“Nothing happens contrary to reason.”

Ethics — Virtue as the Only Good

Chrysippus sharpened Stoic ethics into its most demanding form. Only virtue is good. Only vice is bad. Everything else — wealth, health, reputation, pain, pleasure — belongs to the category of “indifferents.” They matter pragmatically, but they do not determine moral worth.

Emotions, in this framework, are not irrational forces imposed on us, but mistaken judgments about value. Anger, fear, and grief arise when we falsely believe externals can harm our true self. Philosophy, then, becomes cognitive therapy — a training of judgment.

“No man is free who is not master of himself.”

A Machine of Thought and Ink

Chrysippus was astonishingly prolific. Ancient sources credit him with over 700 works, many written at breakneck speed, often arguing both sides of a position to stress-test every assumption. None survive intact, but fragments preserved by later authors reveal a mind obsessed with precision.

His style was sometimes mocked as dry or pedantic, but its influence was total. Later Stoics — including Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius — inherited a system already fortified against centuries of criticism.

“Philosophy is not ornament, but armor.”

Legacy — The Mind Behind the Movement

Chrysippus is rarely quoted, seldom dramatized, and almost never romanticized — yet his influence is foundational. He transformed Stoicism from an ethical attitude into a comprehensive worldview: logical, physical, and moral.

If Stoicism endured for centuries — shaping Roman law, early Christianity, Enlightenment ethics, and modern cognitive therapy — it is because Chrysippus gave it an internal coherence strong enough to survive the erosion of time.

“To live well is to reason well.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia