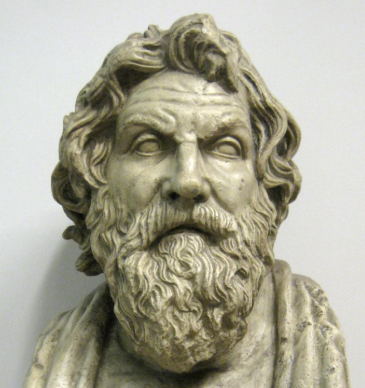

Antisthenes — The Philosopher Who Stripped Life Down to Its Bones (c. 445–365 BCE)

Antisthenes was philosophy with the comforts removed. A student of Socrates and the spiritual ancestor of Cynicism, he believed that virtue needs nothing beyond itself — no wealth, no reputation, no elaborate theory. Truth, for Antisthenes, was not something to admire from a distance but something to live, endure, and embody.

A Student of Socrates, Not of Society

Born in Athens to a non-citizen mother, Antisthenes grew up on the margins of Athenian respectability. This outsider status shaped both his character and his philosophy. He studied rhetoric before encountering Socrates, whose indifference to wealth and status permanently redirected his life.

After Socrates’ execution, Antisthenes became one of his most uncompromising heirs. He rejected Plato’s metaphysical ambitions and Aristotle’s systematic refinements. Philosophy, he insisted, was not a theoretical science but a discipline of character.

“Virtue is sufficient in itself for happiness.”

Virtue Without Ornament

Antisthenes taught that virtue is practical, teachable, and independent of external goods. Wealth, honor, pleasure, and political power are distractions at best and corruptions at worst. The good life requires discipline, endurance, and clarity — not fortune.

This was a direct challenge to Athenian values. Where others sought success or admiration, Antisthenes praised toughness of soul. The truly free person is the one who needs the least.

“I would rather go mad than feel pleasure.”

Against Abstract Theory

Antisthenes was deeply suspicious of abstraction. He famously rejected Plato’s theory of Forms, arguing that definitions beyond concrete things dissolve into empty words. You can show a horse, he claimed, but you cannot show “horseness.”

Language, in his view, should clarify life, not float above it. Knowledge divorced from action is not wisdom but ornament.

“I see a horse, but I do not see horseness.”

The Birth of Cynicism

Antisthenes did not live in a barrel — that honor belonged to his more theatrical successor, Diogenes — but he laid the philosophical groundwork for Cynicism. His emphasis on self-sufficiency, rejection of convention, and contempt for artificial needs became defining Cynic traits.

The Cynic way of life was not nihilistic. It was ethical minimalism: remove what is unnecessary, and virtue stands revealed.

“The wise man is self-sufficient.”

Strength Over Pleasure

Antisthenes believed that pleasure weakens character. True happiness arises from strength — the ability to endure hardship without complaint. This outlook made him austere, even harsh, but also radically free.

His ideal human being is unbribable, unflatterable, and immune to misfortune — not because nothing happens to them, but because nothing owns them.

“Suffering becomes beautiful when anyone bears great calamities with cheerfulness.”

Legacy — Philosophy as Resistance

Antisthenes left no grand system and founded no academy. His legacy lives instead in a posture — resistance to luxury, suspicion of empty talk, and loyalty to virtue alone.

Through Diogenes, his ideas flowed into Stoicism, shaping thinkers from Epictetus to Marcus Aurelius. Antisthenes reminds philosophy of its oldest task: not to impress, but to fortify the soul.

“Better to be mad than delighted.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia