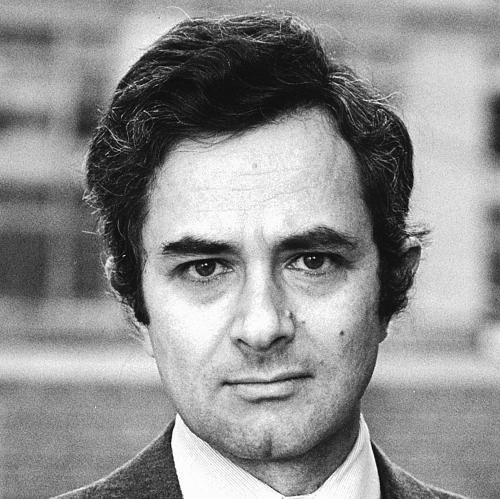

Thomas Nagel — The Philosopher of Subjectivity and the Limits of Objectivity (1937– )

Thomas Nagel is the philosopher who refused to let philosophy forget the first-person point of view. In an age dominated by reductionism and scientific confidence, he persistently asked an unsettling question: what is left out when we explain the world entirely from the outside? His work probes consciousness, ethics, and meaning with quiet rigor and moral seriousness.

A Mind Drawn to the Inescapable “I”

Born in Belgrade and raised in the United States, Nagel came of age intellectually during the rise of analytic philosophy and scientific naturalism. Educated at Cornell, Oxford, and Harvard, he trained in the sharp tools of analytic argument while developing a distinctive philosophical temperament: patient, lucid, and deeply resistant to oversimplification.

From early on, Nagel was drawn to problems that could not be dissolved by clever definitions. He suspected that philosophy’s deepest questions — about mind, value, and meaning — persist precisely because they resist full objectification.

“The view from nowhere is not a human view.”

What Is It Like to Be a Bat?

Nagel’s most famous essay, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” (1974), became an instant classic by stating a simple but devastating point. No matter how much we know about the brain, there remains something it is like to be a conscious creature — a subjective character of experience that cannot be captured by objective description alone.

Even if neuroscience explained every neural mechanism of echolocation, we would still not know what it is like to experience the world as a bat. This gap, Nagel argued, exposes a fundamental limit of reductionist theories of mind.

“An organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism.”

Objectivity, Subjectivity, and the Human Standpoint

Nagel did not reject objectivity — he believed it was one of humanity’s greatest intellectual achievements. But he argued that objectivity is always partial. The more we move toward a “view from nowhere,” the more we risk losing what makes human life intelligible from the inside.

In The View from Nowhere, he explored the tension between our personal perspective and the impersonal demands of reason. Ethics, meaning, and even rationality itself, he argued, live in this unresolved space between the subjective and the objective.

“A fully objective view would leave no one there to take it.”

Ethics, Altruism, and Moral Reality

In moral philosophy, Nagel defended the reality of ethical reasons without grounding them in either divine command or social convention. He argued that reasons can be objective — that some actions are wrong regardless of personal desire or cultural approval.

His work on altruism challenged egoistic accounts of motivation, insisting that we are capable of recognizing reasons that apply to us simply because they apply to anyone. Moral reasoning, for Nagel, extends the self outward rather than dissolving it.

“Reason is not just a servant of desire.”

Mind, Cosmos, and Controversy

In Mind and Cosmos, Nagel reignited debate by questioning whether a purely materialist, Darwinian account of nature can fully explain consciousness, cognition, and value. He did not argue for theism or intelligent design, but suggested that the natural order may include principles not yet understood.

The book drew sharp criticism, but it exemplified Nagel’s intellectual courage: a willingness to admit explanatory gaps rather than paper them over with confidence.

“The world is an astonishing place.”

Legacy — Philosophy Without Consolation

Nagel’s philosophy offers no final synthesis, no comforting metaphysical closure. Instead, it insists on honesty about what we know, what we can explain, and what stubbornly resists explanation.

He remains one of the clearest voices reminding philosophy that consciousness, value, and meaning cannot be eliminated — only confronted. His work stands as a model of intellectual humility paired with relentless clarity.

“The attempt to view the world impersonally is itself a human achievement.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia