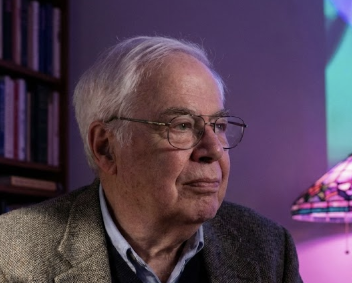

Richard Rorty — The Philosopher Who Let Go of Truth to Save Liberalism (1931–2007)

Richard Rorty was a philosophical disrupter with a gentle smile. He challenged one of Western philosophy’s deepest instincts — the search for objective, timeless Truth — and suggested that we might live better without it. His work reframed philosophy as a cultural conversation rather than a tribunal of reason, trading certainty for solidarity and foundations for hope.

From Analytic Prodigy to Philosophical Heretic

Born in New York City to politically engaged, leftist parents, Rorty grew up steeped in books, debates, and moral seriousness. He trained in the most rigorous style of mid-20th-century analytic philosophy, earning his PhD at Yale and becoming a respected figure in philosophy of mind and language.

For years, Rorty played the game by the rules — clarity, argument, precision. Then he began to suspect that the game itself was the problem. The traditional philosophical quest for foundations, he concluded, was less a path to truth than a relic of theological longing.

“The world does not speak. Only we do.”

Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature — Breaking the Spell

Rorty’s most famous book, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979), detonated a quiet bomb beneath modern philosophy. He attacked the idea that the mind mirrors reality and that knowledge consists in accurately representing the world.

This “mirror” model, he argued, underwrites the obsession with certainty, foundations, and epistemology. Once abandoned, philosophy no longer needs to justify science, morality, or truth. It can instead become what it always secretly was: a conversation about how to live.

“Truth is what your contemporaries let you get away with.”

Pragmatism Without Foundations

Rorty revived American pragmatism — drawing on William James, John Dewey, and a liberal dose of Wittgenstein and Nietzsche. He rejected the idea that beliefs are true because they correspond to reality. Instead, beliefs are tools: they are “true” insofar as they help us cope, cooperate, and flourish.

Knowledge becomes a matter of social justification rather than metaphysical accuracy. Language is not a window onto reality, but a set of evolving vocabularies we invent to solve problems. There is no final vocabulary — only better or worse ways of speaking for particular purposes.

“Take care of freedom, and truth will take care of itself.”

Irony, Contingency, and the Liberal Self

In Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, Rorty offered a vision of the “liberal ironist” — someone who knows their deepest beliefs are historically contingent, yet remains passionately committed to reducing cruelty and expanding freedom.

Irony, for Rorty, is not cynicism. It is the humility to recognize that one’s moral language has no cosmic guarantee. Solidarity arises not from shared rational foundations, but from imaginative identification with the suffering of others.

“Cruelty is the worst thing we do.”

Literature Over Theory

Rorty famously argued that novels, journalism, and history do more moral work than philosophy. Thinkers like Orwell, Nabokov, and Dickens, he believed, expanded moral imagination better than abstract ethical systems.

Philosophy’s task, then, is not to legislate truth but to keep conversation going — to redescribe the world in ways that make cruelty harder and freedom more attractive.

“The hope is that we might become less cruel, not more accurate.”

Legacy — The Anti-Philosopher Philosopher

Rorty infuriated traditional philosophers and inspired countless others. Critics accused him of relativism and complacency; admirers saw him as a liberator who freed philosophy from impossible expectations.

His influence spans philosophy, political theory, literary studies, and public intellectual life. He left behind no system — only a style: conversational, hopeful, anti-authoritarian, and stubbornly committed to liberal democracy without metaphysical crutches.

“There is nothing deep down inside us except what we have put there ourselves.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia