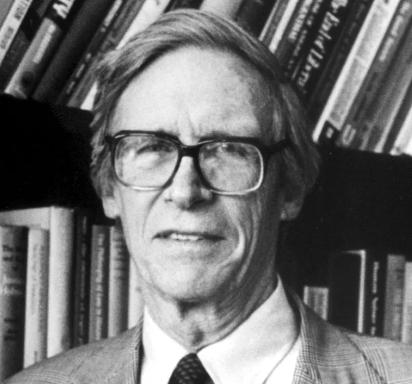

Architect of Justice as Fairness and the Revival of Political Philosophy

1921–2002

John Rawls rescued political philosophy from decades of decline and gave liberal democracy its most powerful theoretical defense. His A Theory of Justice asked the most fundamental question: what principles should govern a just society? His answer—built on the thought experiment of the "original position"—reshaped how philosophers, economists, and policymakers think about fairness, equality, and the obligations we owe each other.

War, Loss, and the Question of Justice

Born in Baltimore to a prominent family, Rawls's early life was marked by tragedy. Two of his brothers died from diseases they contracted from him—events that left deep psychological scars. He studied philosophy at Princeton, but World War II interrupted his academic path. Serving in the Pacific, he witnessed the aftermath of Hiroshima and experienced the moral complexities of warfare firsthand.

These experiences shaped his conviction that philosophy must address real human suffering and injustice. He briefly considered theology, preparing for ministry, but ultimately abandoned faith after witnessing the war's horrors. If there was to be justice, humans would have to create it themselves through reason and mutual commitment.

Justice is the first virtue of social institutions, as truth is of systems of thought.

The Original Position — Philosophy Behind a Veil

Rawls's breakthrough was asking: what principles of justice would we choose if we didn't know our place in society? Imagine yourself behind a "veil of ignorance"—unaware of your race, class, gender, talents, or values. What rules would you accept for organizing society, knowing you might end up anywhere within it?

This thought experiment brilliantly models impartiality. Unable to design rules favoring yourself (since you don't know who you'll be), you're forced to consider everyone's perspective. The original position isn't a historical claim about social contracts but a device for moral reasoning—a way to think about fairness by temporarily setting aside our partial interests and identities.

Each person possesses an inviolability founded on justice that even the welfare of society as a whole cannot override.

Two Principles of Justice

From behind the veil of ignorance, Rawls argued, we would choose two principles. First: equal basic liberties for all—freedom of speech, religion, political participation, and so forth. These liberties are fundamental and cannot be traded away for economic gain or social welfare. The first principle takes absolute priority.

Second: social and economic inequalities are acceptable only if they (a) benefit the least advantaged members of society, and (b) attach to positions open to all under fair equality of opportunity. This "difference principle" permits inequality only when it improves the condition of those worst off. Wealth concentration is just only if it helps, not harms, the poor.

All social values—liberty and opportunity, income and wealth, and the social bases of self-respect—are to be distributed equally unless an unequal distribution of any, or all, of these values is to everyone's advantage.

Justice Versus Utilitarianism

Rawls explicitly challenged utilitarianism, which judges actions and policies by whether they maximize overall happiness or welfare. The problem: utilitarianism can justify sacrificing individuals for the greater good. If enslaving a minority increased total happiness, utilitarianism might endorse it. Rawls found this morally intolerable.

Justice as fairness treats persons as ends in themselves, not mere vessels for happiness to be aggregated. Each person has inviolable rights that cannot be overridden by appeals to social utility. This Kantian foundation—respecting the separate existence of persons—gives Rawls's theory its moral power against purely consequentialist thinking.

The principles of justice are chosen behind a veil of ignorance.

The Difference Principle and Economic Justice

The difference principle radically reframes debates about inequality. It doesn't demand absolute equality—talented people may earn more—but it insists that inequalities must work to everyone's benefit, especially the disadvantaged. Wealth isn't justified by desert or natural talent but by its consequences for social cooperation.

This challenges both libertarian and socialist intuitions. Against libertarians, Rawls argued that natural talents are morally arbitrary—we don't deserve our genes or upbringing. Against socialists demanding strict equality, he allowed inequalities that incentivize productivity benefiting everyone. The question isn't whether inequality exists but whether it serves justice.

The natural distribution is neither just nor unjust; nor is it unjust that persons are born into society at some particular position. These are simply natural facts. What is just and unjust is the way that institutions deal with these facts.

Primary Goods and Self-Respect

Rawls identified "primary goods"—things rational persons want regardless of their particular life plans: rights, liberties, opportunities, income, wealth, and crucially, the social bases of self-respect. This last item reveals his deep concern for human dignity. Justice isn't merely about distributing resources but ensuring everyone can pursue their conception of the good life with dignity.

Self-respect depends on social arrangements that affirm our worth as equals. Institutions that humiliate the poor, exclude minorities, or treat some citizens as second-class violate justice even if they distribute material goods generously. Justice requires not just economic fairness but public recognition of equal moral standing.

Self-respect is perhaps the most important primary good.

Political Liberalism and Reasonable Pluralism

Later in his career, Rawls confronted a challenge: modern democracies contain citizens with incompatible religious, philosophical, and moral views. How can such diverse people agree on principles of justice? His answer: political liberalism seeks principles that reasonable people can endorse despite their deep disagreements about the good life.

Justice must be "freestanding"—not dependent on any particular comprehensive doctrine. We don't need to agree about God, human nature, or ultimate values to agree on fair terms of social cooperation. This "overlapping consensus" respects pluralism while establishing stable, legitimate political authority. Each person can endorse justice from within their own worldview.

A just society is a society that if you knew everything about it, you'd be willing to enter it in a random place.

Public Reason and Democratic Legitimacy

Rawls argued that in constitutional democracies, citizens owe each other justifications for coercive laws that appeal to shared public values, not sectarian doctrines. When debating fundamental matters—constitutional essentials and basic justice—we should offer reasons all reasonable citizens can accept, not appeal to religious revelation or controversial philosophical claims.

This doesn't require abandoning personal convictions in private life, only recognizing that political power in a democracy must be exercised in ways all citizens can reasonably accept. Public reason respects citizens as free and equal by not imposing some people's comprehensive doctrines on others through state force.

The idea of public reason specifies at the deepest level the basic moral and political values that are to determine a constitutional democratic government's relation to its citizens.

Legacy — Justice as the Foundation

Rawls died in 2002, but A Theory of Justice remains the most important work of political philosophy in the twentieth century. He made justice intellectually respectable again, showing that careful reasoning about fairness could yield substantive conclusions. He gave egalitarian liberalism its most sophisticated defense while taking seriously objections from libertarians, communitarians, and utilitarians.

Beyond academic philosophy, Rawls influenced constitutional law, economics, and policy debates about healthcare, education, and welfare. His framework for thinking about justice—asking what principles we'd accept from behind a veil of ignorance—has become a standard tool for moral reasoning. In an age of growing inequality and political polarization, his insistence that justice requires attending to the least advantaged remains powerfully relevant.

The sense of justice is continuous with the love of mankind.

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia