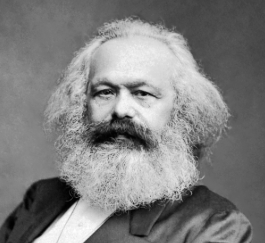

Karl Marx — The Critic of Capital, Class, and the Machinery of Modern Life (1818–1883)

Marx was a volcanic force in 19th-century thought — part economist, part historian, part revolutionary philosopher. He sought not merely to interpret the world but to expose its hidden structures and change them. His ideas reshaped politics, economics, and social theory in ways no other modern thinker has matched.

A Restless Mind in an Age of Upheaval

Born in Trier, Germany, Marx came of age during industrialization’s roar — smokestacks, railways, and vast factories transforming Europe with dizzying speed. He immersed himself in philosophy at the University of Berlin, drawn to German Idealism but increasingly dissatisfied with abstractions that hovered above real human suffering.

Journalism became his battleground. His critiques of political repression and economic injustice eventually forced him into exile, first in Paris, then Brussels, and finally London, where he spent decades researching in the British Museum while living in near poverty with his family.

“Philosophers have only interpreted the world; the point is to change it.”

Historical Materialism — The Engine of Social Change

Marx proposed that human societies evolve not primarily through ideas but through material conditions — the organization of labor, technology, and economic relations. This view, known as historical materialism, treats history as a dynamic struggle shaped by how people produce and distribute the necessities of life.

For Marx, every era carries internal tensions: classes with opposed interests locked in a long, grinding conflict that eventually forces society to transform. Ancient slavery gave way to feudalism; feudalism to capitalism; and capitalism, he argued, would one day give way to something beyond it.

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

Capitalism — Innovation Paired with Exploitation

Marx admired capitalism’s dynamism — its ability to revolutionize technology, reshape the globe, and unleash unprecedented productivity. Yet he believed this came at a profound human cost. Workers were alienated: from the products they made, from their own creativity, from one another, and from the very process of labor.

In Capital, his monumental analysis, Marx dissected the mechanisms of markets, profit, and labor. He argued that capitalists extract “surplus value” from workers, creating wealth for a few and precarious existence for the many. This economic imbalance, he predicted, would intensify until capitalism undermined itself.

“Capital is dead labour which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour.”

Revolution, Emancipation, and the Cooperative Future

Working closely with Friedrich Engels, Marx developed the vision of a society beyond class domination. He believed the working class — the proletariat — would eventually rise to overturn the structures that exploited them and build a more egalitarian form of social life.

This new society would be cooperative rather than competitive, organized around shared control of productive resources and the full development of human potential rather than the pursuit of profit.

“From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

Legacy — A Thinker Who Redrew the Political Map

Marx’s ideas inspired revolutions, political movements, and intellectual traditions across the world. Some applications of his thought led to liberation movements; others hardened into authoritarian regimes that departed sharply from his humanistic aims. Yet even his critics grapple with his insights into power, economy, and social change.

In economics, sociology, political theory, and cultural criticism, Marx remains a towering figure. His analysis of alienation, class, and ideology continues to illuminate the structures of modern life — and provoke debates about justice, freedom, and the possibilities of a more humane society.

“The oppressed are allowed once every few years to decide which particular representatives of the oppressing class are to misrepresent them.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia