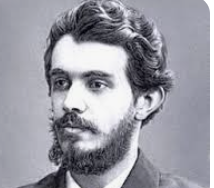

Nikolai Berdyaev — The Philosopher of Freedom, Spirit, and Creative Personhood (1874–1948)

Nikolai Berdyaev was the great metaphysical rebel of modern Russian thought — a philosopher who believed that freedom precedes being, spirit outruns systems, and personality is more fundamental than nature, society, or law. Against determinism, collectivism, and abstract rationalism, Berdyaev insisted that the deepest truth of existence is the irreducible freedom of the human person. Philosophy, for him, was not analysis alone, but a spiritual struggle against necessity.

From Marxism to Spiritual Revolt

Born into an aristocratic military family in Kiev, Berdyaev initially embraced Marxism as a critique of social injustice and oppression. He was arrested and exiled by the Tsarist regime for revolutionary activity — an experience that shaped his lifelong hostility to authoritarian power.

Yet Berdyaev soon broke with Marxism itself. He came to see materialism and historical determinism as new forms of spiritual enslavement. Any system that reduces the human being to economics, biology, or social role, he believed, destroys the core of personhood.

True liberation, he concluded, must be spiritual before it can ever be political.

“Freedom is not a right; it is a duty.”

Freedom Before Being

Berdyaev’s most radical claim overturns the foundations of traditional metaphysics: freedom is not derived from being — being itself arises from freedom.

He rejected the idea that reality is governed by fixed laws, rational necessity, or divine determinism. At the root of existence, Berdyaev posited an abyss of freedom — a primordial groundlessness from which creativity, personality, and history emerge.

This freedom is terrifying as well as liberating. It is the source of evil as well as good. But without it, no genuine creativity or moral responsibility is possible.

“Freedom is the source of tragedy, but also of dignity.”

Personhood Against Objectification

Berdyaev drew a sharp distinction between person and object. Objects belong to the realm of necessity — they can be classified, controlled, and used.

Persons, by contrast, are inward, unrepeatable, and creative. They cannot be reduced to roles, functions, or identities imposed from outside. Any society that treats people as means — whether capitalist, socialist, or technocratic — commits a metaphysical crime.

True community, Berdyaev argued, arises not from uniformity or coercion, but from free spiritual communion between persons.

“The person is never a means; the person is an end.”

Creativity as a Spiritual Calling

For Berdyaev, creativity is not optional. It is the vocation of humanity. To exist authentically is to participate in the unfinished creation of the world.

He believed that God does not dominate creation from above, but calls human beings into co-creation — inviting freedom, risk, and novelty. History is therefore not merely repetition or decay, but an open drama whose outcome is not guaranteed.

Art, philosophy, love, and moral action are all expressions of this creative response to freedom.

“Man is called not only to be saved, but to create.”

Revolution, Exile, and Spiritual Resistance

Berdyaev initially welcomed the Russian Revolution as a liberation from tyranny, but quickly recognized its totalitarian trajectory. Bolshevism, he argued, replaced economic exploitation with spiritual enslavement.

In 1922, he was expelled from Soviet Russia on the infamous “philosophers’ ship,” along with other dissident intellectuals. Exile became the defining condition of his life — both geographically and spiritually.

In the West, Berdyaev continued to write as a Christian existentialist fiercely opposed to both capitalist commodification and communist collectivism.

Christianity Without Domination

Berdyaev’s Christianity was deeply unorthodox. He rejected legalism, institutional authority, and punitive conceptions of God.

Faith, for him, was not submission, but liberation — the affirmation of freedom, love, and creative spirit against the forces of objectification.

The Kingdom of God, he believed, is not a political system or future utopia, but a spiritual reality breaking into history through free persons.

Legacy — The Prophet of Personalist Freedom

Berdyaev stands apart from both analytic philosophy and systematic metaphysics. He belongs instead to a lineage of prophetic thinkers — alongside Dostoevsky, Kierkegaard, and Simone Weil — who treat philosophy as a matter of ultimate concern.

His influence can be felt in existentialism, personalism, liberation theology, and critiques of totalitarian modernity. He remains a fierce reminder that freedom is dangerous, creativity is risky, and dignity cannot be engineered.

For Berdyaev, the tragedy of history is real — but so is the promise of spirit.

“The problem of freedom is the fundamental problem of philosophy.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia