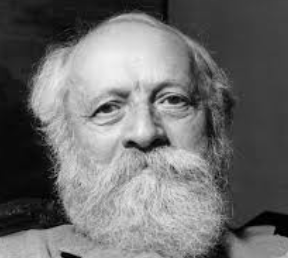

Martin Buber — Dialogue, Relation, and the Sacred Between (1878–1965)

Martin Buber was the philosopher of relation — a thinker who claimed that human life is not primarily about isolated minds confronting objects, but about encounters between living beings. For Buber, meaning arises not inside the self alone, but in the space where one person truly meets another.

A Life Between Cultures and Traditions

Born in Vienna and raised partly by his grandfather, a renowned scholar of Jewish tradition, Buber grew up immersed in religious texts and storytelling. He later studied philosophy, psychology, and art history, moving freely between spiritual and secular worlds.

This lifelong crossing of boundaries shaped his philosophy: he refused to separate religion from daily life or metaphysics from ordinary human relationships.

“All real living is meeting.”

I–It and I–Thou — Two Ways of Being in the World

Buber’s most famous distinction is between two basic modes of relation: I–It and I–Thou. In the I–It mode, we treat the world as a collection of objects to be used, analyzed, classified, and controlled.

This mode is necessary for science and practical life, but it reduces others to things. The I–Thou relation, by contrast, is a meeting between whole beings, without manipulation or distance.

In I–Thou, the other is not experienced as an object, but as a presence.

“In every Thou we address the eternal Thou.”

Dialogue as an Existential Event

Dialogue, for Buber, is not merely conversation. It is an existential stance of openness and presence. One can speak endlessly without entering dialogue, or remain silent while fully encountering another.

True dialogue requires risk: the willingness to be affected, to be changed by the encounter.

Relation, not reflection, becomes the birthplace of meaning.

“The real struggle is not between East and West or capitalism and communism, but between relation and isolation.”

God as Relation, Not Object

Buber’s religious philosophy rejected the idea of God as an object of theological speculation. God is not something we can analyze or define.

Instead, God is encountered in the deepest form of relation — in the ultimate I–Thou. Religious life becomes not belief in doctrines, but responsiveness to presence.

Faith, in this sense, is lived dialogue, not abstract certainty.

“God is not an object beside objects, but the eternal partner in dialogue.”

Politics, Zionism, and Binational Hope

Buber was deeply engaged in political life and supported Jewish cultural renewal in Palestine, yet he opposed nationalism that erased the dignity of others.

He advocated for Jewish–Arab coexistence based on mutual recognition rather than domination.

Political structures, he believed, must grow from genuine human relations, not replace them.

Influence and Philosophical Neighbors

Buber influenced existentialists, theologians, educators, and dialogue theorists across disciplines. His work resonates with thinkers such as Levinas, though Buber emphasized reciprocity while others stressed ethical asymmetry.

His ideas continue to shape psychotherapy, conflict resolution, and religious thought.

Legacy — Meaning in the Space Between

Buber’s philosophy resists both technical domination and romantic isolation. He insists that human beings become fully real only through relation.

The self is not a sealed container. It is a crossing point of encounters.

In a world increasingly mediated by screens and systems, Buber’s message remains quietly radical: presence still matters.

“The world is not comprehensible, but it is embraceable.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia