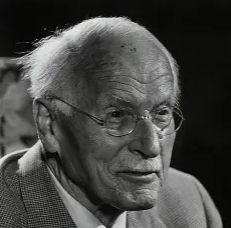

Carl Gustav Jung — Explorer of the Psyche and Cartographer of the Unconscious (1875–1961)

Carl Gustav Jung was the great myth-maker of modern psychology — a thinker who refused to reduce the human mind to instinct, mechanism, or pathology. Where others saw superstition, Jung saw symbols. Where others saw neurosis, he saw meaning struggling to be born. His work stands at the strange crossroads of science, philosophy, religion, and art, insisting that the human psyche is deeper, older, and stranger than modern rationalism allows.

From Medicine to the Depths of the Mind

Jung was born in Switzerland into a family steeped in theology, an inheritance that left him acutely aware of religion’s psychological power even as its doctrines began to crumble under modern scrutiny. Trained as a physician and psychiatrist, Jung initially approached the mind through empirical research, working at the Burghölzli psychiatric hospital under Eugen Bleuler.

Early in his career, Jung conducted word-association experiments that revealed emotionally charged clusters of ideas he called complexes. These findings convinced him that the unconscious was not merely a repository of forgotten memories, but an active force shaping thought, emotion, and behavior.

“The unconscious is not just evil by nature, it is also the source of the highest good.”

Freud, the Break, and a New Psychology

Jung’s early alliance with Sigmund Freud seemed, for a time, to promise a unified science of the mind. Freud saw in Jung a successor; Jung saw in Freud a powerful but narrowing vision. The rupture was inevitable.

Jung rejected Freud’s insistence that sexuality was the primary driver of psychic life. He believed Freud had mistaken one powerful current for the whole ocean. The break was not merely personal — it marked the birth of analytical psychology, a framework that treated the psyche as symbolic, creative, and future-oriented.

“Freud is the man who discovered the cellar. I discovered that there is also an upper story.”

The Collective Unconscious and Archetypes

Jung’s most radical contribution was the idea of the collective unconscious — a deep layer of the psyche shared by all humans, shaped not by personal experience but by evolutionary history. This layer expresses itself through archetypes, universal patterns that structure myths, dreams, religions, and art.

Figures such as the Shadow, the Anima and Animus, the Hero, the Trickster, and the Wise Old Man are not inherited images but inherited forms — psychological tendencies that organize experience long before conscious thought intervenes.

“Myths are public dreams. Dreams are private myths.”

Individuation — Becoming Who You Are

At the heart of Jung’s psychology lies the process of individuation, the lifelong task of integrating the conscious and unconscious aspects of the self. This is not self-improvement or social success, but a difficult confrontation with one’s inner contradictions, shadows, and unrealized potentials.

Individuation requires facing what society encourages us to deny — weakness, irrationality, and inner conflict. For Jung, neurosis often arose not from excess repression alone, but from a failure to live in accordance with one’s deeper nature.

“One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious.”

Alchemy, Religion, and the Symbolic World

Jung’s later work ventured far beyond the boundaries of conventional psychology. He explored alchemy, Gnosticism, Eastern religions, and medieval symbolism, arguing that these traditions encoded psychological truths in symbolic rather than scientific language.

His controversial concept of synchronicity — meaningful coincidence without causal explanation — challenged strict materialism and suggested that psyche and world may be linked through patterns rather than mechanisms.

“We are not today what we were yesterday, nor shall we be tomorrow what we are today.”

Legacy — Meaning Against Reduction

Jung remains a deeply polarizing figure. To critics, he strayed too far into mysticism. To admirers, he restored depth, symbolism, and soul to a psychology in danger of becoming mechanical.

His legacy endures wherever human beings refuse to believe that their dreams are meaningless, their myths disposable, or their inner lives reducible to chemistry alone. Jung’s enduring challenge is simple and unsettling: the psyche is vast, ancient, and unfinished — and ignoring it comes at a cost.

“The meeting of two personalities is like the contact of two chemical substances: if there is any reaction, both are transformed.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia