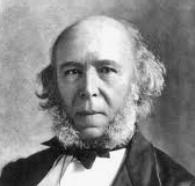

Herbert Spencer — The Philosopher of Evolution, Society, and Unintended Consequences (1820–1903)

Herbert Spencer was one of the most influential — and most controversial — thinkers of the nineteenth century. Long before Darwin’s ideas reshaped biology, Spencer attempted something even more audacious: to explain the evolution of everything. Nature, mind, morality, politics, and society itself, he argued, follow the same underlying principles of development. His sweeping system helped define Victorian thought and left a legacy that still provokes debate today.

A Self-Taught System Builder

Born in Derby, England, Spencer received little formal education. Instead, he educated himself through reading, engineering work, and relentless intellectual curiosity. This independence shaped his philosophy: he distrusted authority, institutions, and tradition, believing progress emerged from spontaneous order rather than centralized control.

Spencer began his career as a railway engineer, a background that deeply influenced his mechanical and systemic view of society. Gradually, philosophy overtook engineering, and he devoted his life to constructing a unified explanation of the natural and social world — an ambition few thinkers have dared to attempt.

“The great aim of education is not knowledge but action.”

Evolution Before Darwin — From Simple to Complex

Spencer developed his theory of evolution independently of Charles Darwin. While Darwin focused on biological species, Spencer applied evolutionary principles to the entire universe. Evolution, for Spencer, was the movement from simplicity to complexity, from homogeneity to differentiation, driven by natural processes rather than divine design.

He famously coined the phrase “survival of the fittest,” intending it as a neutral description of adaptive processes — though the phrase would later take on far darker political meanings. To Spencer, evolution explained not only life, but the growth of language, morality, intelligence, and social institutions.

“Progress is not an accident, but a necessity.”

Society as an Organism

Spencer’s most famous and contentious idea was his comparison of society to a living organism. Just as biological organisms evolve specialized organs, societies develop institutions — economic, political, cultural — that perform distinct functions.

Crucially, Spencer argued that healthy societies evolve naturally. Attempts to forcibly reshape society through government intervention, he warned, risk disrupting complex systems whose consequences cannot be fully predicted. This view led him to champion individual liberty and oppose extensive state welfare, regulation, and centralized planning.

“Society exists for the benefit of its members, not its members for the benefit of society.”

Ethics, Individualism, and Controversy

Spencer believed morality itself evolves. Ethical behavior, he argued, emerges as societies become more peaceful and cooperative. Over time, individuals internalize social norms that promote mutual survival and flourishing.

However, his opposition to social welfare programs and his belief that suffering could play a role in social adaptation made his ideas deeply controversial. Later thinkers and policymakers distorted his views into what became known as “Social Darwinism” — a label Spencer himself rejected but could never fully escape.

“The ultimate end of human progress is the achievement of happiness.”

The Synthetic Philosophy — Explaining Everything

Spencer’s life work, known as the Synthetic Philosophy, attempted to integrate biology, psychology, sociology, ethics, and metaphysics into one coherent system governed by evolutionary laws. It was one of the most ambitious intellectual projects of the nineteenth century.

For decades, Spencer was among the most widely read philosophers in the English-speaking world. His books sold in enormous numbers, shaping public discourse on science, politics, and progress at the height of the Industrial Age.

“There is a principle which is a bar against all information… the principle of contempt prior to investigation.”

Legacy — A Giant with a Complicated Shadow

Spencer’s reputation declined sharply in the twentieth century, as his ideas became associated with inequality, laissez-faire dogma, and misapplications of evolutionary theory. Yet many of his insights — about complexity, unintended consequences, and the limits of centralized control — remain strikingly relevant.

He stands as a cautionary figure: a reminder of both the power and the danger of grand systems. Spencer sought to explain the whole world, and in doing so, revealed how deeply philosophy can shape — and misshape — society itself.

“Life is the continuous adjustment of internal relations to external relations.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia