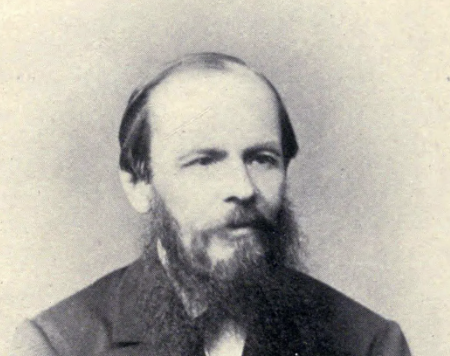

Fyodor Dostoyevsky — The Novelist Who Descended into the Human Soul (1821–1881)

Dostoyevsky did not write philosophy as argument — he wrote it as lived catastrophe. His novels plunge into guilt, freedom, faith, nihilism, and redemption, staging philosophical ideas as moral crises inside desperate human beings. More than any thinker of the modern age, he revealed what happens when ideas collide with suffering souls.

Early Promise and Catastrophic Interruption

Born in Moscow to a strict and emotionally volatile household, Dostoyevsky grew up amid poverty, illness, and religious tension. He trained as an engineer but quickly turned to literature, achieving early success with Poor Folk, which won praise for its compassion toward society’s forgotten.

That promising ascent ended abruptly. In 1849, Dostoyevsky was arrested for participating in a radical intellectual circle. After months in prison, he was led before a firing squad — only to receive a last-second commutation to hard labor in Siberia. The experience permanently transformed his understanding of freedom, suffering, and faith.

“To live without hope is to cease to live.”

Siberia — Suffering as Revelation

Dostoyevsky spent four years in a Siberian prison camp, followed by years of compulsory military service. There, surrounded by criminals and peasants, he encountered a raw humanity untouched by intellectual abstraction.

He later wrote that suffering is not merely accidental to human life but a condition through which self-knowledge becomes possible. This conviction would become central to his novels: redemption is not achieved by reason alone, but through humility, endurance, and compassion.

“Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart.”

Freedom, Guilt, and the Psychology of Crime

In Crime and Punishment, Dostoyevsky explores the modern temptation to justify evil through ideology. Raskolnikov believes himself exempt from moral law — until guilt shatters his rationalizations.

The novel dismantles utilitarian and nihilistic ethics from the inside. Crime is not undone by cleverness, but by confession and moral reckoning. Freedom divorced from responsibility becomes torment.

“If there is no God, everything is permitted.”

The Underground — Consciousness Turned Against Itself

Notes from Underground introduces one of literature’s most disturbing figures: a narrator hyper-aware, resentful, and self-sabotaging. He rejects rational progress, scientific optimism, and any system that claims to explain human behavior.

Dostoyevsky saw clearly that humans often act not for happiness or uti

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia