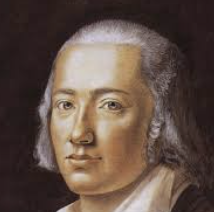

Friedrich Hölderlin — Poetry at the Edge of Philosophy and Madness (1770–1843)

Hölderlin stands at a fault line in European thought — where philosophy strains toward poetry, where reason fractures under the weight of the infinite, and where language itself becomes a metaphysical experiment. He was not merely a poet who read philosophy; he was a thinker who tried to say what philosophy could only gesture toward.

A Mind Formed Among Titans

Hölderlin studied at the Tübinger Stift alongside Hegel and Schelling. The three shared an obsession with Greek antiquity, freedom, and the limits of Enlightenment rationality. While Hegel built systems and Schelling pursued nature philosophy, Hölderlin took a more dangerous path — dissolving philosophy into lyric vision.

He absorbed Kant’s critical limits, Fichte’s radical subjectivity, and the Greek sense of cosmic order, but refused to reduce existence to concepts. Where philosophy sought closure, Hölderlin insisted on openness.

“Full of merit, yet poetically, man dwells on this earth.”

The Tragic Split — Gods and Mortals

At the core of Hölderlin’s thought lies a wound: the separation between the divine and the human. Ancient Greece represented a lost harmony — gods walked among mortals, meaning was woven into nature itself. Modernity, by contrast, is an age of abandonment.

The gods have withdrawn. Humanity is left with reason, technology, and history — powerful tools, but incapable of restoring sacred unity. Hölderlin did not romanticize this loss; he felt it as an existential catastrophe.

“Where danger is, grows the saving power also.”

Poetry as Ontology

For Hölderlin, poetry was not ornament or expression. It was a way of revealing being itself. Language, when pushed to its limits, could momentarily reunite what history had torn apart — human and divine, time and eternity, self and world.

This made poetry a sacred task. The poet becomes a mediator, speaking in fragments, aware that clarity would be a betrayal. Truth arrives not as explanation, but as resonance.

“Poetry is the beginning and end of philosophy.”

Love, Revolution, and Collapse

Hölderlin’s life mirrored his thought — intense, idealistic, and unsustainable. His love for Susette Gontard, immortalized as “Diotima,” became both inspiration and torment. He embraced the French Revolution in its early promise, seeing in it the possibility of historical renewal.

Both hopes collapsed. Political terror replaced liberation. Love became impossible. His mental health deteriorated, culminating in a breakdown that ended his public life in his early thirties.

“I am nothing; what I seek is everything.”

The Tower Years

Hölderlin spent the last 36 years of his life in near silence, living in a tower overlooking the Neckar River. Declared incurably mad, he wrote occasional poems under strange pseudonyms, dated decades into the future or past.

Whether these years were pure illness or a withdrawal from unbearable clarity remains debated. What is certain is that his greatest recognition came long after his voice faded.

Legacy — The Poet Heidegger Could Not Escape

Hölderlin became a central figure for Heidegger, who saw in him the thinker of Being that philosophy had failed to become. Modern poets, existentialists, and phenomenologists found in Hölderlin a language capable of naming absence itself.

He remains a figure of warning and promise: a reminder that reason alone cannot house the human spirit, and that approaching the infinite always carries a cost. Hölderlin shows what happens when thought refuses safety and insists on dwelling where meaning trembles.

“Man dwells poetically — even in an age that has forgotten the gods.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia