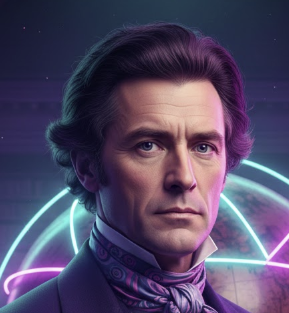

Alexis de Tocqueville — The Anatomist of Democracy’s Soul (1805–1859)

Alexis de Tocqueville was not a cheerleader for democracy nor its enemy, but its most perceptive diagnostician. He approached political life as a social scientist before the term existed, probing beneath laws and institutions to uncover habits, beliefs, and quiet assumptions. His enduring insight was unsettling: democracy is not merely a system of government, but a way of life that reshapes how people think, feel, and relate to one another.

An Aristocrat Studying Equality

Born into a Norman aristocratic family marked by the trauma of the French Revolution, Tocqueville inherited both privilege and historical anxiety. His parents narrowly escaped the guillotine, and the collapse of the old order haunted his political imagination. Rather than resisting the rise of equality, Tocqueville chose to understand it.

Trained as a magistrate, he believed that political stability depended less on constitutions than on customs. Laws could be copied; social habits could not. This conviction would shape his life’s work.

“The past no longer illuminates the future; the mind of man wanders in obscurity.”

Democracy in America — A Mirror Held to the Modern World

In 1831, Tocqueville traveled to the United States, officially to study prison reform. Unofficially, he observed everything. The result was Democracy in America, one of the most penetrating analyses of modern society ever written.

Tocqueville saw American democracy as both astonishing and dangerous. Its strength lay in local self-government, voluntary associations, and a culture of civic participation. Its weakness lay in conformity, mediocrity, and the quiet pressure of majority opinion.

“I know of no country in which there is so little independence of mind and real freedom of discussion as in America.”

The Tyranny of the Majority

Tocqueville’s most famous warning was not about kings or dictators, but about the moral pressure exerted by democratic majorities. In democratic societies, power rarely crushes bodies — it disciplines minds.

He feared a future in which citizens surrendered judgment for comfort, exchanging liberty for security, and independence for sameness. This danger did not announce itself with violence; it arrived politely, gradually, and with good intentions.

“The tyranny of the majority leaves the body alone. It goes straight for the soul.”

Individualism and Soft Despotism

Tocqueville distinguished individualism from selfishness. Individualism, he argued, is a democratic withdrawal — a retreat into private life as public responsibility erodes. When citizens disengage, power quietly centralizes.

The result is what Tocqueville called “soft despotism”: a paternalistic state that manages life gently, reducing citizens to passive dependents. Freedom disappears not through chains, but through comfort.

“It covers the surface of society with a network of small complicated rules… it does not break wills, but it softens them.”

Religion, Liberty, and Moral Limits

Tocqueville believed religion played a paradoxical role in democracy. Though separate from the state, it sustained moral restraint and prevented freedom from collapsing into license. Religion, he argued, taught citizens self-limitation — a virtue democracy desperately needs.

He did not defend theology as truth, but as a social necessity. A society without shared moral horizons drifts toward coercion or decay.

“Despotism may govern without faith, but liberty cannot.”

Legacy — Democracy’s Most Honest Friend

Tocqueville was neither nostalgic for aristocracy nor naive about equality. He accepted democracy as inevitable — and insisted it must be cultivated deliberately or it would rot from within.

His work continues to illuminate modern anxieties: mass culture, conformity, bureaucratic overreach, and the erosion of civic life. Tocqueville did not tell democracies what they want to hear — he told them what they must remember.

“Liberty cannot be established without morality, nor morality without faith.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia