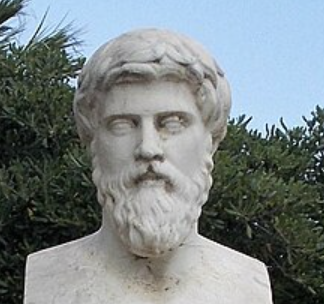

Plutarch — The Moral Biographer of Character and Civic Life (c. 46–120 CE)

Plutarch stands at a crossroads where philosophy meets history and ethics meets storytelling. Neither a system-builder nor a skeptic, he believed that the study of lives— their virtues, vices, and turning points— is the most practical way to understand moral truth. His work treats character as destiny and biography as a mirror for self-examination.

A Greek Thinker in a Roman World

Born in Chaeronea, a small town in Boeotia, Plutarch was Greek by culture and education, yet he lived under Roman rule and moved comfortably within Roman elite society. He studied philosophy in Athens, traveled widely, and later served as a priest at the Oracle of Delphi.

This dual identity shaped his outlook. Plutarch admired Roman civic virtue and political seriousness, while remaining deeply committed to Greek philosophy and literary tradition. His work aims to reconcile power with wisdom and action with moral reflection.

“The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.”

Parallel Lives — History as Moral Comparison

Plutarch’s most famous work, the Parallel Lives, pairs Greek and Roman figures—Theseus with Romulus, Pericles with Fabius Maximus, Alexander with Julius Caesar— and compares their characters rather than their achievements.

He is explicit about his aim. He is not writing history in the strict sense, but moral biography. A small gesture, an offhand remark, or a private failure can reveal more about a person’s soul than a battlefield victory.

“It is not histories that I am writing, but lives.”

Ethics Without a System

Philosophically, Plutarch was a Platonist, but not a rigid one. He drew freely from Aristotle, the Stoics, and common moral intuition. His concern was not theoretical purity, but practical wisdom—how to live well within families, cities, and imperfect political systems.

In his essays, collected as the Moralia, he writes on friendship, superstition, education, political participation, and the control of anger. The tone is humane, reflective, and corrective rather than dogmatic.

“An imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal ailment of all republics.”

Religion, Reason, and Moderation

As a priest at Delphi, Plutarch took religion seriously, but he opposed superstition as vigorously as atheism. He believed the divine was real, yet best approached through reason, moderation, and ethical improvement.

For him, philosophy was a civilizing force: it tamed fear, restrained excess, and aligned human life with cosmic order. Extremes—whether political, emotional, or religious— were signs of intellectual and moral failure.

“Superstition is an excess of fear, while atheism is a deficiency of sense.”

Legacy — Character as the Core of History

Plutarch shaped how the West remembers antiquity. Shakespeare, Montaigne, and Rousseau all drew heavily from him. Through Plutarch, Greek and Roman figures became moral exemplars— not marble statues, but flawed humans whose choices still instruct.

His enduring message is simple and demanding: history matters because character matters, and character is revealed not in grand theories, but in how power, fortune, and temptation are handled.

“The measure of a man is the way he bears prosperity and adversity.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia