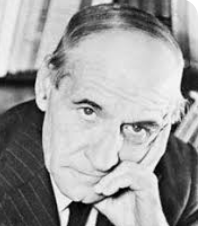

José Ortega y Gasset — The Philosopher of Life, Circumstance, and Historical Reason (1883–1955)

José Ortega y Gasset was the philosopher of situated existence — a thinker who refused to separate the self from the world it inhabits. Against abstract systems and timeless truths, Ortega insisted that human life is always lived from within a concrete situation. We do not first exist and then acquire circumstances; we exist only as beings embedded in history, culture, and personal fate.

A Philosopher in a Nation in Crisis

Born in Madrid into a family of journalists and intellectuals, Ortega grew up immersed in political debate and cultural reform. Spain at the turn of the twentieth century was struggling with decline, lost empire, and social stagnation.

Ortega believed philosophy had a civic mission: to diagnose cultural illness and stimulate renewal. He saw himself not as a detached academic, but as a public intellectual addressing the fate of his society.

“I am myself and my circumstance, and if I do not save it, I do not save myself.”

Life as the Radical Reality

Ortega rejected both pure idealism and crude materialism. Neither mind alone nor matter alone, he argued, captures what is most basic. The fundamental reality is my life — the lived drama of choosing, acting, and responding to the world.

Life is not something we observe from the outside. We are always already inside it, committed to projects, surrounded by constraints, forced to decide without complete knowledge.

Philosophy must therefore begin from lived experience, not from abstract categories.

“Living is feeling oneself forced to decide what we are going to be.”

Perspectivism — Truth Has Many Angles

Ortega developed a doctrine of perspectivism: every individual apprehends reality from a unique position. No single viewpoint exhausts the truth, yet each genuine perspective reveals something real.

This was not relativism. Ortega did not believe all opinions are equally valid. Instead, truth emerges from the integration of perspectives, much as a landscape requires multiple vantage points to be fully seen.

Knowledge is therefore historical and social, not the possession of isolated minds.

“Each life is a point of view upon the universe.”

Historical Reason Instead of Pure Reason

Ortega criticized the philosophical tradition for treating reason as timeless and universal. Human thinking, he argued, always operates within history.

He proposed historical reason: a form of understanding that explains beliefs, values, and institutions by tracing how they emerge from concrete life situations.

To understand a person or a society is to understand the story that produced them.

“Man has no nature; what he has is history.”

The Revolt of the Masses

Ortega’s most famous book, The Revolt of the Masses, diagnosed what he saw as a new social type: the mass man — confident, technologically empowered, yet lacking cultural discipline and historical awareness.

He worried that mass society would flatten excellence, replace thoughtful leadership with complacent conformity, and turn democracy into mediocrity by sheer numerical force.

His critique was not anti-democratic in principle, but a warning that democracy requires cultivated citizens, not merely counted ones.

Exile and European Vision

The Spanish Civil War forced Ortega into exile. He lived in France, Argentina, and Portugal, continuing to lecture and write about Europe’s crisis of meaning.

Long before political union became feasible, Ortega argued for a shared European consciousness — a recognition that national destinies were historically intertwined.

Europe, for him, was not merely a geography, but a cultural project in need of renewal.

Legacy — Philosophy from Within Life

Ortega stands at the crossroads of existentialism, phenomenology, and historicism. He influenced thinkers from Julián Marías to Hannah Arendt, and helped bring continental philosophy into Spanish intellectual life.

His enduring message is simple and demanding: philosophy must begin where we already are — in the middle of our lives, entangled in circumstances, responsible for choices we cannot escape.

We are not spectators of reality. We are participants in a story that is still being written.

“Life is not a matter of having or not having; it is a matter of deciding.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia