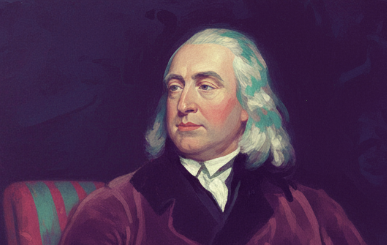

Jeremy Bentham — Architect of Utilitarianism and Reformer of Modern Society (1748–1832)

Bentham believed that philosophy should not merely interpret the world but improve it. His radical, rational, and often eccentric mind sought one guiding principle to shape laws and institutions: maximize happiness, minimize suffering. Few thinkers have left such a deep imprint on modern ethics, politics, and legal reform.

A Prodigy with a Reformer's Heart

Born in London to a family of lawyers, Bentham was a child prodigy who read serious works of history and philosophy before most children can manage basic arithmetic. He entered Oxford at twelve and soon developed a distaste for the traditions and formalities of academic life, preferring the clarity of reason to inherited authority.

As he matured, Bentham became convinced that the legal and political systems of his day were irrational, inconsistent, and unjust. He set out to redesign them from first principles using a scientific approach to human behavior — a startlingly modern ambition for the eighteenth century.

“The greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation.”

The Principle of Utility — A New Moral Compass

Bentham's signature idea, the “principle of utility,” offered a simple criterion for evaluating actions, laws, and institutions: do they promote happiness and reduce suffering? He tried to measure pleasures and pains with almost mathematical precision, proposing a “felicific calculus” to quantify moral choices.

While the calculus itself was more ambitious than practical, the underlying idea reshaped moral and political thought. It provided a secular, empirical foundation for ethics — one grounded not in tradition or divine command but in human well-being.

“Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure.”

Law, Democracy, and Social Reform

Bentham was a relentless advocate for legal transparency, equality before the law, and democratic accountability. He opposed hereditary privilege, championed universal suffrage, and supported freedom of expression at a time when these ideas were seen as dangerously radical.

His critiques of harsh punishments, prison conditions, and state secrecy helped shape later reforms in criminal justice. He even designed the famous “Panopticon” prison — a circular structure allowing inmates to be observed at all times — as a way to improve efficiency and reduce cruelty, though it later took on darker symbolic meanings in modern theory.

“Every law is an infraction of liberty.”

Bentham’s Eccentric Vision for a Better World

Bentham’s creativity and oddity went hand in hand. He campaigned for animal welfare, birth control, decriminalization of same-sex relationships, and the expansion of education — causes far ahead of his time. His belief that the moral community should expand to all beings capable of suffering remains a guiding light for animal rights movements.

In true Benthamite fashion, even his death became a philosophical gesture: he requested his body be preserved and displayed as an “auto-icon,” still viewable today at University College London — a final argument for transparency and reason over superstition.

“The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”

Legacy — The Birth of Modern Utilitarianism

Bentham’s rational, reformist spirit shaped modern democratic institutions, human rights debates, economic policy, and legal philosophy. His influence extends through John Stuart Mill, the development of welfare economics, and contemporary discussions of policy ethics.

By grounding morality in measurable well-being, Bentham gave modern society one of its most enduring tools for thinking about justice. His legacy endures wherever policymakers ask a deceptively simple question: What will make life better for the people affected?

“Stretching his hand up to reach the stars, too often man forgets the flowers at his feet.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia