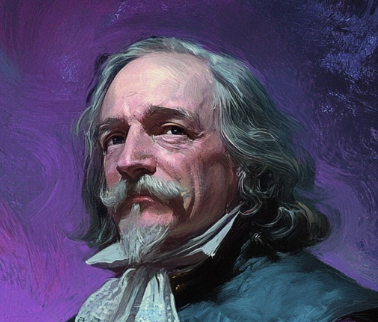

Thomas Hobbes — Architect of the Modern State and Theorist of Human Nature (1588–1679)

A philosopher forged in an age of civil war, Thomas Hobbes sought certainty in a world of chaos. His relentless analysis of fear, power, and human desire produced one of the most influential — and controversial — political visions in Western history.

Born in a Time of Upheaval

Hobbes entered the world during the Spanish Armada crisis of 1588, later saying that his mother gave birth to him and fear at the same time. This dramatic origin story captures the tenor of the era he lived through: political violence, religious conflict, and the long shadow of civil war in England.

Educated at Oxford and later employed as a tutor to the aristocratic Cavendish family, Hobbes traveled across Europe, meeting leading scientists and thinkers. These journeys nourished his fascination with geometry, physics, and the emerging scientific method — influences that shaped his vision of society as something that could be explained with the clarity of natural law.

“Fear and I were born twins together.”

The State of Nature — A World Without Authority

Hobbes’s most famous idea is his account of the “state of nature,” a hypothetical condition where no government or law exists. In this environment, he argued, humans are driven by self-preservation, competition, and distrust.

Life in such a world, he wrote, would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” The vivid harshness of this description was not pessimism for its own sake — it was Hobbes’s way of diagnosing the real causes of conflict and demonstrating why political authority is necessary.

“The condition of man... is a condition of war of every one against every one.”

Leviathan — The Birth of Sovereignty

Hobbes’s masterpiece, Leviathan (1651), is a sweeping attempt to construct a political system on rational foundations. To escape the chaos of the state of nature, individuals enter a social contract, surrendering some freedoms to an authority capable of enforcing peace.

This sovereign — whether monarch, parliament, or assembly — must wield enough power to prevent society from collapsing into conflict. Hobbes was not glorifying tyranny; he was arguing that stability and security are the first conditions of a functioning society. Without them, even liberty becomes impossible.

“Covenants, without the sword, are but words.”

Materialism, Motion, and the Science of Politics

Hobbes’s philosophy was unapologetically materialist. He believed everything — thought, emotion, will — could be explained as motion of matter. This mechanistic worldview led him to analyze politics scientifically, treating human behavior as something predictable, even calculable.

His approach influenced generations of political thinkers, economists, and social scientists seeking to understand complex human systems without appealing to divine or mystical explanations.

“Science is the knowledge of consequences.”

Legacy — The Dark Mirror of Political Philosophy

Hobbes remains one of the most contested thinkers in history. Critics say he reduces human beings to fearful automatons; admirers praise his honesty about power, conflict, and the fragility of order. Both sides agree that his ideas set the stage for modern political theory.

His insistence that government’s legitimacy rests not on divine right but on human agreement reshaped the foundations of political authority. Every debate about social contracts, state power, security, and individual rights bears the imprint of Hobbes’s fierce, unflinching vision.

“The obligation of subjects to the sovereign is understood to last only so long as the power lasts by which he is able to protect them.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia