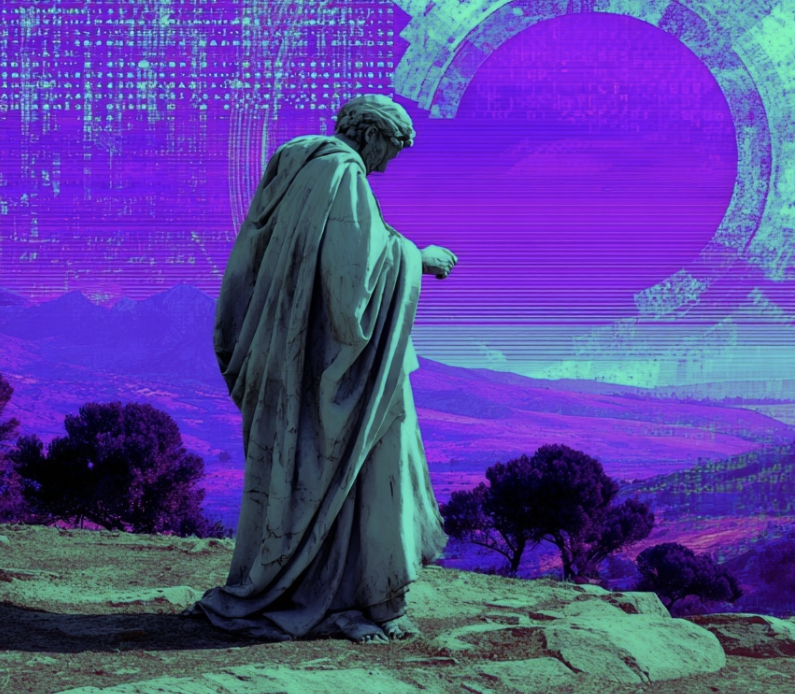

Boethius — The Philosopher Between Worlds (c. 477–524 CE)

A Roman statesman, scholar, and prisoner who wrote one of the most influential works in Western philosophy — blending classical reason with early medieval faith.

Life in a Collapsing Empire

Boethius was born into a powerful Roman family during the turbulent years after the fall of the Western Empire. Although Rome had crumbled politically, its intellectual traditions still lived, and his early education immersed him in Greek philosophy, mathematics, and literature. His ambition was bold: to translate all of Aristotle and Plato into Latin and preserve classical thought for the future.

He rose to high office under King Theodoric the Ostrogoth, serving as consul and later as a senior adviser. His political career, however, placed him at the center of court intrigue — and would ultimately destroy him.

“Nothing is miserable unless you think it so.”

Fall From Power and Imprisonment

In 523 CE, Boethius was accused of treason — likely a political fabrication — and thrown into prison. Stripped of status, separated from his family, and awaiting execution, he turned inward. Out of that suffering emerged one of history’s most remarkable books: The Consolation of Philosophy.

It was written without access to scripture, relying entirely on reason, classical ethics, and poetic reflection. In his cell, he argued with Lady Philosophy herself, a personification of wisdom who guides him toward clarity.

“In all adversity, the greatest misfortune is to have once been happy.”

The Consolation of Philosophy

This work blends prose and poetry, weaving Stoicism, Neoplatonism, and his own reflections. It explores the nature of fortune, happiness, free will, fate, and God’s relationship to time. His central claim is that true happiness springs from what cannot be taken away — virtue, wisdom, and the alignment of the soul with the eternal.

He rejects the idea that external success defines a person. Power, wealth, and reputation are like the wheel of Fortune: always turning, never stable. Philosophy offers a more lasting foundation.

“The good is the position of calm stability; evil is a restless storm.”

Fate, Providence, and Freedom

One of Boethius’s most influential ideas is his distinction between providence and fate. Providence is the eternal, all-encompassing perspective of the divine. Fate is the unfolding of events within time — a partial, moment-by-moment aspect of that greater pattern.

This insight allowed him to reconcile human freedom with a structured cosmos: we act freely within time, while the divine sees all outcomes at once, outside time’s flow. Centuries of Christian, Islamic, and medieval thinkers built upon this framework.

“Eternity is the whole, simultaneous, and perfect possession of everlasting life.”

Legacy

Boethius’s writings became foundational for medieval philosophy. For almost a thousand years, The Consolation of Philosophy was one of the most widely read books in Europe — shaping Dante, Chaucer, Aquinas, and countless scholars. His translations of Aristotle preserved logic for the medieval curriculum.

He stands as a bridge between the ancient and medieval worlds, the last Roman philosopher and the first major thinker of the Middle Ages. His voice echoes with the calm endurance of someone who sought meaning even as his world dissolved around him.

“Who would give a law to lovers? Love is unto itself a higher law.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia